Art's Abstract Thinking Is an Evolutionary Adaptation

/When I’m writing fiction, my brain works differently than when I’m writing non-fiction. I see the world more vividly, and I see stories exploding out of everything—apartment buildings, rusty swing sets, abandoned cars. Why?

Researchers using brain-scanning technologies have begun to answer this question and many others. They’re finding data to back the long-held notion that the arts are crucial to human cognitive development and abilities throughout life.

The Running Human

How did the modern human mind develop? One possibility: abstract thinking, developed during persistence hunting.

Simply put, humans are the best long-distance runners on the planet—nothing with four legs can keep up over marathon and ultra-marathon distances. Don’t believe me? Read the history of the Western States 100 endurance race (the picture above), which started out as a horse race until humans started running and winning it.

Long story short, four-legged animals have their air and cooling system tied to their locomotion system: one stride per one breath (watch a cheetah run in slow motion; it’s like a squeaky toy). Whereas our air and cooling system is separate from our locomotion system (two to three strides per breath), and with many, many more sweat glands.

Ever have your dog sit down on a hot day in the shade and refuse to keep walking?

Four-legged animals have to regulate their heat mostly through their breath, which is tied to their stride—which means they eventually have to stop to cool down. Humans, however, can pretty much run forever because our breaths aren’t tied to our strides and we can cool ourselves with far more sweat glands than our furry friends have. Which is why Western States is now an ultra-marathon and not a horse race.

Tarahumara Runner in Mexico’s Copper Canyons, courtesy of A Closer Look Tours

Persistence Hunting and Abstract Thought

In a persistence hunt, hunters basically run an animal to exhaustion, then walk up and kill it. It takes three to five hours on average (coincidentally or not, about the time it takes most humans to run a modern marathon). And, according to theory, it’s maybe how we developed our brains.

Tracking requires not only observation and deduction; it requires imagination. For example, gazelles are fast enough to run out of sight, so hunting them takes tracking skills. But tracking is also about predicting where the animal is going—abstract thought.

Even after you learn to read dirt…the next level is tracking without tracks, a higher state of reasoning known in the lit as “speculative hunting.” The only way you can pull it off…was by projecting yourself out of the present and into the future, transporting yourself into the mind of the animal you’re tracking...Visualization…empathy…abstract thinking and forward projection: aside from the kneeling-over part, isn’t that exactly the mental engineering we now use for science, medicine, the creative arts?

—Christopher McDougall, Born to Run

“Art accesses some of the most advanced processes of human intuitive analysis and expressivity, and a key form of aesthetic appreciation is through embodied cognition, the ability to project oneself as an agent in the depicted scene,” says Christopher Tyler, director of the Smith-Kettlewell Brain Imaging Center.

Picasso, Figures at the Seaside, courtesy of ideelart

The Road to Picasso

According to the American Association of School Administrators (AASA), humans make neural connections at a rapid rate when we’re young, and the play activities we do when we’re young contribute to the development of those connections:

Much of what young children do as play—singing, drawing, dancing—are natural forms of art. These activities engage all the senses and wire the brain for successful learning…

These cerebral talents are the result of many centuries of interaction between humans and their environment…The arts are not just expressive and affective, they are deeply cognitive. They develop essential thinking tools—pattern recognition and development; mental representations of what is observed or imagined; symbolic, allegorical and metaphorical representations; careful observation of the world; and abstraction from complexity.

But it’s not just when we’re young. The connections we make when we’re young help us throughout our lives. Keeping those connections active is just as important.

“We have found,” reports Northwestern University researcher Nina Kraus (via the AAAS). “And others have found, that musicians have stronger auditory and listening cognitive skills across the lifespan…To sum things up, we are what we do, and our past shapes our present. Auditory biology is not frozen in time. It’s a moving target. And music education really does seem to enhance communication by strengthening language skills.”

According to Hyperallergic, creating art can improve brain function even in retirees:

Researchers discovered “a significant improvement in psychological resilience” among those who participated in drawing and painting classes; they did not find it in the art-appreciation group. What’s more, the fMRI scans of the art-class group also showed improved “effective interaction” between certain regions of the brain known as the default mode network. This area is associated with cognitive process like introspection, self-monitoring, and memory. Since connectivity in this area decreases in old age, it’s possible that art could reverse and even stop its decay.

Art Is a Survival Adaptation

Other recent fMRI studies have demonstrated enhancements in the functional connectivity between the frontal, posterior, and temporal cortices after the combination of physical exercises and cognitive training.

—How Art Changes Your Brain: Differential Effects of Visual Art Production and Cognitive Art Evaluation on Functional Brain Connectivity.

The combination of physical exercises and cognitive training…Such as tracking a gazelle for three or four hours, maybe?

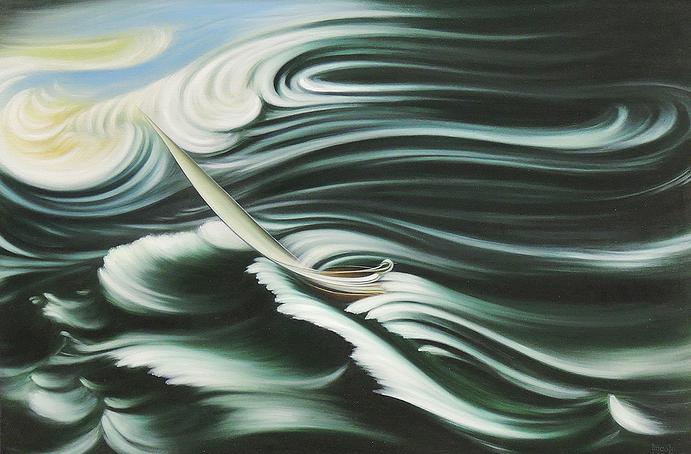

Ben Lincoln, Perseverance

"When you're doing art, your brain is running full speed," Gary Vikan, Director of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, told the AAAS. "It's hitting on all eight cylinders. So if you can figure out what's happening to the brain on art, you know a whole lot about the brain."

In essence, creating art appears to increase brain development when we’re young and brain functioning when we’re old. So, what may have begun as a survival adaptation has apparently remained a survival adaptation.